One Thousand White Women:

A Novel

by Jim Fergus

(St. Martin’s Press, 1998)

Based on an historical (although disputed) event, the request of a Northern Cheyenne chief at a Fort Laramie peace conference in 1854 to send one thousand white women as brides for his young warriors to unite the two cultures, Jim Fergus creatively expands on this premise in his novel One Thousand White Women. Although the United States did not accept this offer of assimilation, Fergus imagines what would have happened if this exchange had actually taken place in a fictional journal penned by one of the brides.

The Introduction and Epilogue of the novel constitute a frame story told by the great-grandson of the protagonist, May Dodd. J. Will Dodd has become intrigued with the family history about his crazy ancestor who was committed to an insane asylum and then ran off to join the Indians. After he finds an old letter written to her children, his grandfather, he begins to research the events, eventually discovering the journals May Dodd keeps of her time living with the Northern Cheyenne.

The main plot begins with May preparing to go West as a part of a contingent of women taking part in a noble experiment: “To foster harmony and understanding among the races–the melding of future generations into one people” (73). The theory was that since the Cheyenne are a matrilineal society, all of the children born of the unions would become a part of the mother’s “tribe.” That is, they would be considered and accepted as whites.

The government secretly begins gathering the women, mostly from insane asylums and jails, who will be traded for horses. May’s wealthy, socialite family has committed May into an insane asylum because she fell in love with a working man. Worse, she darkened the family name by living with him outside of marriage and bearing two children. To “save” the children, her father has her imprisoned because of her “promiscuous behavior.” She is confined to bed, subjected to inhumane treatments, and sexually abused. When the opportunity to escape arises, she signs up for the program immediately, circumventing her father’s approval.

What begins as an experiment in the assimilation of the Cheyenne into white civilization becomes an interesting study of the assimilation of the white women into the Cheyenne way of life as they become a part of the Native culture and eventually bear their children. Slowly but steadily, the women come to respect the Cheyenne people, thrive in their marriages, and become an integral part of the tribe. The characters in the novel, especially the women, are interesting and diverse. I admired the women as they struggle to adjust to a completely foreign way of life as well as deal with the conflicts of a life close to nature, and I respected the Cheyenne for accepting the white women as members of the tribe, despite their differences. As the narrative unfolds, the daily life, customs, and spirituality of the Cheyenne are rendered faithfully and in detail.

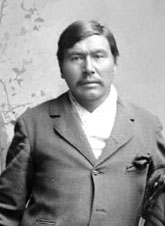

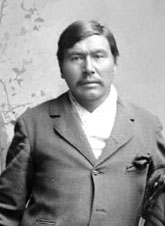

Jules Seminole (Smithsonian)

However, a couple of elements of the novel disturbed me. One was the scene where the Southern and Northern Cheyenne gather for feasting and dancing, and the half-breed Jules Seminole (an historical interpreter) trades whiskey to the men and women. Granted, alcohol consumption and the negative effects it had on American Indians did occur and often, but Fergus grossly exaggerates the sex and violence, perhaps to increase book sales for twenty-first century readers who have grown accustomed to and expect such graphic scenes. He describes it as a drunken orgy. “Throngs of drunken savages, men and women, jostled me as I pushed by. Naked couples copulated on the ground like animals. . . . It was as if the whole world had fallen from grace, and we had been abandoned to witness its final degradation” (224). Many of the white women cowered in the ineffectual priest’s tent as women were raped all over the camp. Granted, Fergus may have been attempting to evade the Noble Savage stereotype and present the Cheyenne as “real people,” but the wholesale drunkenness of the camp is unrealistic. Unfortunately, the disturbing scene of the raid on the Shoshone, the enemies of the Cheyenne, when the right hands of twelve children were brought back as trophies of war to strengthen their own children, is based on fact. The Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution in 1892-1893 records this event.

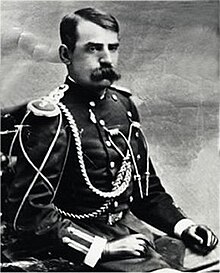

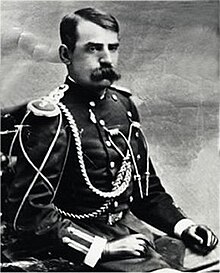

Captain John Gregory Bourke

I also could not empathize with the main characters, May Dodd or her lover, Captain Bourke (yet another historical figure). Throughout the novel, May lavishes praise on the Cheyenne people and their way of life and is accepted unconditionally by her husband, his family, and the tribe, yet she continues to call them “savages” throughout the novel. As the story progresses, she does begin to alternate between calling them “savages” and “the People,” the term they use to identify themselves, and she refuses to leave before she fulfills her promise to the government, but she always lapses back into her “civilized thinking.” Even toward the end of the narrative, she calls her unborn child a “savage baby” (366). She intends to convince her husband Little Wolf and his people to move to the reservation where she can continue her charge to civilize, Christianize, and assimilate the Cheyenne. Her goal is to put in the two years she promised, have her Cheyenne baby, and then return to her own “real” children. Throughout the novel, I was waiting for her to see the awful truth of the situation, that the Cheyenne society was more civilized than white society, and to become one with the Cheyenne people, but she never did.

However, as much as I could not respect May or her captain, I do believe that they realistically personify the mindset of many Americans at the time, who believed that “the best Indian is a dead Indian.” As Captain Burke explains to May, “The savages are not just a race separate from ours; they are a species distinct. . . . pagans who have never evolved beyond their original place in the animal kingdom, have never been uplifted by the beauty and nobility of civilization. They have no religion beyond superstition, no art beyond stick figures scratched on rock, no music besides that made by beating on a drum. They do not read or write” (107). Others believed that what needed to be done was follow Richard Pratt’s belief: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” No matter how much May admired the Cheyenne, she could not stop viewing them as “Other.” This ethnic prejudice continues today.

When the destruction of the Cheyenne is eminent, Bourke wants to save May, but none of the other white women nor the innocent Cheyenne people, and he ultimately kills Horse Boy in cold blood. Perhaps that is Fergus’s intent; by contrasting the truly civilized Cheyenne with the self-seeking and barbarian whites, we more fully understand the true horror of America’s treatment of our Native people.

In my opinion, the strongest character in the novel was the mulatto Euphemia Washington, “Phemie,” who is a descendant of African Ashanti warriors. Having been a slave and raped by her master, she joins the tribe and marries on her terms, becoming a respected woman warrior, riding bare-breasted into battle like an Amazon. She also serves as a foil, countering May’s idealism with reality. “Absorbed? Assimilated? Hardly. Our common history is one of dispossession, murder, and slavery.” When May protests, saying that the children will be the hope for the future, Phemie sets her straight. “The plantations were full of mulattos–people of mixed blood and of all shades and colors. I myself am one. I am half-white. My father was the master. Did this make me free? Did this make me accepted by the ‘superior’ culture? No, I was still a slave . . . considered neither black nor white, and resented by both” (357). Sadly, what Phemie predicted came true. Even the children who would later be torn from their parents, shorn of their hair and their culture, and “civilized” in Indian Boarding schools (like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School), were not accepted by the white culture and forced to return to the reservation where they no longer fit in or speak the language of their families.

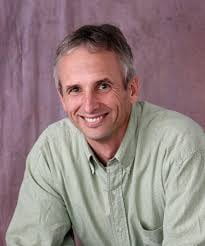

Cheyenne Chief Little Wolf

May’s Cheyenne husband, Little Wolf, chief of the Northern Cheyenne, was also an actual chief who played an important role in Western American history, and he, too, is depicted accurately. Although the army attack on the winter encampment is dated in May Dodd’s journal as March 1, 1876, the actual massacre on the combined Dull Knife and Little Wolf camp on the Powder River actually occurred on November 25, 1876, exactly five months after the defeat of Custer at the Little Bighorn. According to the Wyoming State Historical Society, “U.S. troops found them and burned their village to the ground. This little-known battle, referred to as the Dull Knife Fight or the Red Fork Battle, impacted the Cheyenne people during the Indian Wars even more than did the Little Bighorn fight.” Little Wolf was shot seven times but survived. The rest of his story is heartbreaking, and one that even May Dodd foresaw. Eventually Little Wolf, Dull Knife, and their bands had to surrender in 1877 because they were starving. They were promised a reservation on their own lands; unfortunately, the army broke their promise to them again, and sent them to live in the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. After half of the Cheyenne died in 1878, the survivors escaped and headed back to Nebraska. Dull Knife and his band surrendered at Fort Robinson where many of them were later massacred. (This story is told in Mari Sandoz’s Cheyenne Autumn.) Little Wolf hid in the Nebraska Sand Hills and was eventually granted a reservation in Montana.

Jim Fergus Website

I am always interested in how authors transform history into fiction, how they choose which facts to incorporate and which to leave out, and why they sometimes “alter” history. Since so much of One Thousand White Women closely mirrors historical events and people, even in the smallest details of Cheyenne life, I wondered why Fergus would change the date of the massacre on the Powder River, setting it in March rather than in November when it actually happened. My guess is that he set it earlier so that he would not have to include the complex events of the Battle of the Little Bighorn that occurred in June. Both the Sioux and the Cheyenne participated in the event including, most believe, Dull Knife and Little Wolf. That would have made the novel much longer and more complicated. Another reason might be that, according to Fergus’s author website, he is working on the second book in a trilogy to be published in 2016 that will continue the thread of this work. I’ll bet that the Custer defeat will be included in that sequel.

Another historical discrepancy in the novel was the shooting of Jules Seminole by Little Wolf because of lewd remarks to his daughter. In reality, Little Wolf was banished from his people for killing a Cheyenne, but while drunk, and he killed a man called Starving Elk, who was, in fact, harassing his daughter. In this case, it is obvious why Fergus altered these facts! Although I cannot find what actually happened to the real Jules Seminole, he is a character that needed to be killed off!

Although May Dodd’s commitment to an insane asylum was only a small portion of the novel, this, too, is based on historical fact. In writing my second book, Kate Cleary, I did extensive research into nineteenth century asylums. It only took one person to petition to the court for anyone to be committed to an insane asylum and only one vague statement from one doctor after a brief examination to bring the person to a short trial (always men on the jury), which usually resulted in commitment. Along with drug and alcohol addiction, the reasons a person could be placed in an insane asylum included hysteria, menopause, melancholy, smoking, and masterbation! Fathers and husbands, especially those with wealth, had little difficulty in persuading a judge to declare an unsubmissive woman insane.

All in all, One Thousand White Women does an excellent job in describing the courage, dignity, grace, generosity, and selflessness of the Cheyenne culture and the atrocities inflicted upon them, indeed upon all Native people, in the name of Manifest Destiny. That Captain Bourke and May Dodd completely buy into this myth and exhibit the prejudice of their times may cause us to dislike them, but it is a history lesson that we should not forget.

capability” (215). The final paragraph of the Epilogue is outstanding. The last two sentences are as bright and forceful as a strike of lightning: “We need a prophet collaborating with a statesman. Natural rivals, coming together to be revealed as complementary and interdependent” (215). What a perfect ending that sums up the whole book!

capability” (215). The final paragraph of the Epilogue is outstanding. The last two sentences are as bright and forceful as a strike of lightning: “We need a prophet collaborating with a statesman. Natural rivals, coming together to be revealed as complementary and interdependent” (215). What a perfect ending that sums up the whole book!

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me

In an interview on the Harcourt website, Doig describes his style of writing as “poetry under the prose.” He explains that “Rhythm, word choice, and premeditated lyrical intent are the elements of this type of writing. In the diary I kept while working on

In an interview on the Harcourt website, Doig describes his style of writing as “poetry under the prose.” He explains that “Rhythm, word choice, and premeditated lyrical intent are the elements of this type of writing. In the diary I kept while working on

While Doc Susie’s story is interesting and inspiring in itself, author Virginia Cornell’s narrative approach is what makes the biography so compelling. Cornell grew up in Hideaway Park, two miles from Fraser where her parents established Miller’s Idlewild Inn near the West Entrance Portal to the Moffat Tunnel, which figures so prominently in the book . After she received her PhD in Renaissance English Literature from Arizona State University, she returned to manage her family’s ski resort as well as own and edit a small newspaper, the Winter Park Manifest. This fusion of Rocky Mountain resident, research scholar, and popular journalist combines to make Doc Susie one of the most readable and authentic biographies that I have encountered in a long time. First, Cornell knows firsthand the flora, fauna, climate, and personalities that make up small mountain communities, so the setting through which she moves her protagonist comes refreshingly alive. In this description, Cornell describes a barn dance. “Carrying baskets of fried chicken and potato salad into the bright interior of the barn she [Doc Susie] admired the clean-scrubbed pine floor, sprinkled with corn meal so the dancers could spin and shuffle even faster than if the floors had been newly waxed. Evergreen boughs and wildflowers were strung between stall braces. At one end, a planked platform for the musicians had been laid over tree stumps. Walking across the crunchy barn floor Doc enjoyed successive waves of smells: fresh pine, hay, rotted manure, neat’s-foot oil used on tack and harnesses, cinnamon cookies, lemonade”(118).

While Doc Susie’s story is interesting and inspiring in itself, author Virginia Cornell’s narrative approach is what makes the biography so compelling. Cornell grew up in Hideaway Park, two miles from Fraser where her parents established Miller’s Idlewild Inn near the West Entrance Portal to the Moffat Tunnel, which figures so prominently in the book . After she received her PhD in Renaissance English Literature from Arizona State University, she returned to manage her family’s ski resort as well as own and edit a small newspaper, the Winter Park Manifest. This fusion of Rocky Mountain resident, research scholar, and popular journalist combines to make Doc Susie one of the most readable and authentic biographies that I have encountered in a long time. First, Cornell knows firsthand the flora, fauna, climate, and personalities that make up small mountain communities, so the setting through which she moves her protagonist comes refreshingly alive. In this description, Cornell describes a barn dance. “Carrying baskets of fried chicken and potato salad into the bright interior of the barn she [Doc Susie] admired the clean-scrubbed pine floor, sprinkled with corn meal so the dancers could spin and shuffle even faster than if the floors had been newly waxed. Evergreen boughs and wildflowers were strung between stall braces. At one end, a planked platform for the musicians had been laid over tree stumps. Walking across the crunchy barn floor Doc enjoyed successive waves of smells: fresh pine, hay, rotted manure, neat’s-foot oil used on tack and harnesses, cinnamon cookies, lemonade”(118).

The work quickly catches the reader’s interest with two murders in the Prologue. Holm then follows the same format as in The Osage Rose with Daughtery called in on the crime and Hoolie as his sidekick. The men split again, allowing the reader to follow two plot lines with the men and plots converging in the end. The Epilogue, as in the earlier work, ends with Daughtery on trial for the retribution killings discussed in the earlier work.

The work quickly catches the reader’s interest with two murders in the Prologue. Holm then follows the same format as in The Osage Rose with Daughtery called in on the crime and Hoolie as his sidekick. The men split again, allowing the reader to follow two plot lines with the men and plots converging in the end. The Epilogue, as in the earlier work, ends with Daughtery on trial for the retribution killings discussed in the earlier work.

Go Set a Watchman

Go Set a Watchman