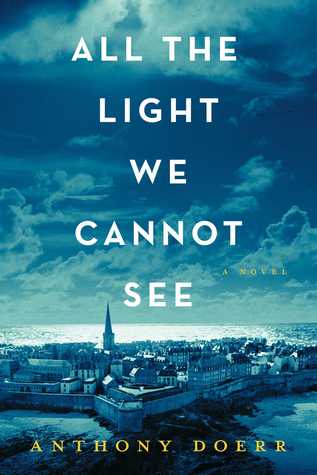

All the Light We Cannot See

All the Light We Cannot See

by Anthony Doerr

(Scribner, 2014)

Because All the Light We Cannot See has been on so many “top ten” lists for 2014, like the New York Times Book Review, Powell’s Books, and Goodreads, because Anthony Doerr has won so many awards, not to mention the 2015 Pulitzer Prize, and because it is historical fiction, when I saw this book for sale at my book store, I grabbed it. Even though I have a stack of “must read” books that have been gathering dust on my bookshelves, I started on it immediately. Although the structure was slightly confusing at first and the characters a little slow to develop, once the momentum picked up, I was hooked and finished it in three sittings.

The story is set in 1944 during World War II in the coastal town of St. Malo, France, as the United States Air Force begins bombing the city which is being occupied by the Nazis. The story then flashes back to 1934, and Doerr introduces us to his two main characters. Marie-Laure LeBlanc, is a six-year-old blind girl being raised by her father, a locksmith for the Museum of Natural History in Paris. For her birthdays, he carves her intricate, wooden puzzles within which he hides gifts. When the Nazis overrun Paris, Marie-Laure and her father flee to St.Malo to take refuge with an eccentric uncle and his long-time housekeeper, one of the leaders of the French Resistance. Meanwhile, Werner Pfennig, a seven-year-old orphan boy, is being raised with his sister, Jutta, in an orphanage in a German mining town. White-haired and blue-eyed, he earns a chance to attend an elite Nazi military school because of his math skills and his genius for working with radios, saving him from a life preordained for the mines like his father, killed in a mining accident. Werner, too, winds up in St. Malo where he is ferreting out and helping destroy Resistance forces. Doerr adds an ailing arch-villain, Sergent van Rumpel, who closes in on Marie-Laure, intent on finding the “Sea of Flames,” a blue diamond with a red center that supposedly grants immortality to its owner–but also misfortune. The reader knows that the lives of these two protagonists will intertwine sooner or later and that van Rumple will be a catalyst. The suspense lies, of course, in how the connections will play out and what will be the result. However compelling the plot, the strength of the novel lies in Doerr’s focus on the inner struggles and maturation of the characters as they strive to overcome their personal handicaps, blindness and poverty, rather than on the military aspects of the war.

The historical elements of the novel interested me. Although the Siege of St. Malo, France, is not a well-known battle of World War II, this historic, walled city was nearly destroyed because of a false report that thousands of Germans were occupying the city. As a result, according to Phillip Beck in the Journal for Historical Review (Winter 1981), “A ring of U.S. mortars showered incendiary shells on the magnificent granite houses, which contained much fine paneling and oak staircases as well as antique furniture and porcelain; zealously guarded by successive generations. Thirty thousand valuable books and manuscripts were lost in the burning of the library and the paper ashes were blown miles out to sea. Of the 865 buildings within the walls only 182 remained standing and all were damaged to some degree.” As the story begins, both Marie-Laure and Werner are enduring the bombing and burning of St. Malo in separate buildings, each confronting imminent death.

I was particularly drawn to the Nazi youth training schools like the National Political Institute of Education at Schulpforta that Werner attended and the influence that it had on spreading racial and political propaganda and in teaching students to love Hitler and to obey to state authority. The National Political Institutes of Education describes the goal of these German schools: to raise a new generation for the political, military, and administrative leadership of the Nazi state. “Thirty such schools, under the direct supervision of the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel), were created by 1941 with over 6,000 students enrolled. Military-style disciple dominated the school where only “racially flawless” boys were admitted after eight days of entrance examinations. Because of the grueling and competitive training, one fifth of all cadets did not succeed, many cause of accidents incurred during training, like the disastrous beating of the “weak,” gentle Frederich. Werner is torn between his desire to avoid being sent to a life underground or to follow his conscience as did his friend Frederich, whose life was destroyed because of his refusal to submit. “Six more times he hears Rodel swing and the hose whistle and the strangely dead smack of the rubber striking Frederich’s hands, shoulders and face. . . . As some point the beating stops. Frederich is facedown in the snow.” Throughout the novel, Werner struggles to make the right choices. In this case, he does not. He “opens his mouth but closes it again; he drowns; he shuts his eyes, his mind” (194). Werner wants to help his friend, but his will to survive overrides his morality.

One intriguing event chronicled in the novel was the rounding up of all French men between the ages of fifteen and sixty and imprisoning them in an historic fort, Fort National. As Beck explains, the fort was in the line of fire between the Americans and the Germans, and eighteen hostages were killed or mortally wounded. Marie-Laure’s uncle, Etienne, is one of the men imprisoned, leaving the blind girl to fend for herself in the war-torn city while being stalked by van Rumpel. After surviving five days alone with little food or water, Marie-Laure finally decides to confront her predator. She “reaches beneath the bench and locates the knife. She crawls along the floor to the top of the seven-rung ladder and sits with her feet dangling and the diamond inside the house in her pocket and the knife in her fist. She says, ‘Come and get me'” (452).

For any writer, trying to figure out how to tell one’s story is the greatest challenge. Whose viewpoint should be used? Should it be first person limited or third person omniscient? Or, how about multiple perspectives, one of the more popular options in today’s literature? And where does one start? At the beginning, in media res, or at the end? The choices Doerr makes to begin at the end and tell the story from multiple viewpoints works perfectly because it not only creates suspense, but it also helps the reader understand the story from opposing sides, the French civilians and the German soldiers.

Thank you for this synopsis! I’ve read the book but had forgotten parts of it. Your description was very helpful in bringing it all back!